This article was originally published in 2011, with updates in 2014 and 2016. It has had a few hits recently, so I’ve updated it again.

This article was originally published in 2011, with updates in 2014 and 2016. It has had a few hits recently, so I’ve updated it again.

Someone found the blog on the search term “adi how to check wing mirror position”. A bit of a strange question if it was from an ADI, but for pupils it is often a problem – certainly to start with.

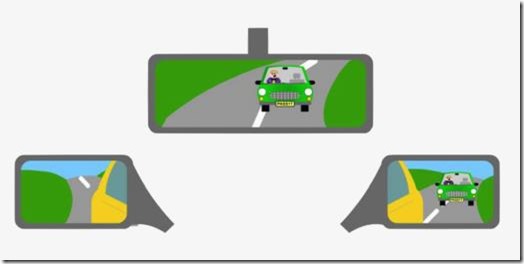

The wing mirrors should be adjusted to give the maximum view behind without creating blind spots. My own lesson plans use the image shown on here. However, this is not intended to provide millimetre-perfect guides for where to put the mirrors!

The bottom line is that you aren’t interested seeing birds and aeroplanes, or road kill. You want to see as much as possible of what is happening behind you and to your sides. You don’t want to be looking at half of your own car. It isn’t rocket science.

I currently teach in a Ford Focus and I’ve found that a good position position for the wing mirrors from the pupil’s position in the driving seat is when they can just see the tip of the front door handle in the extreme bottom right of the nearside mirror, and the extreme bottom left of the offside mirror. Anywhere near that position is fine – it doesn’t have to be measured with a ruler! Obviously, if you’re an ADI using a different car, you set the mirrors yourself and then look for a reference you can explain to your pupils when they have to do it.

One point I do stress to my learners is that if they plan on using the mirrors for any reversing manoeuvres, it makes sense to adjust them consistently each time they get in the car (during their cockpit drill). If they don’t, what they see can vary, leading to confusion.

An ADI needs to have a rough idea of what the best mirror position looks like from the passenger seat so they know if the pupil is doing things properly. This is pretty much down to experience, because all pupils are different – some sit 4 feet behind the steering wheel because they’re 6′ 7″ tall, whereas others sit only a few centimetres away because they’re 4′ 10″. Consequently, the best mirror position for each learner can vary dramatically.

I remember one occasion many years ago when one of my pupils had driven to a location for a manoeuvre. Just before we started it I casually glanced at her offside mirror and something struck me as being odd. I suddenly realised that I could see the side of the car in it from the passenger seat. When I tested the position later I confirmed that she would have been unable to see anything but the side of the car!

Lord knows what she was thinking, or what she thought she was seeing. She’d been through her cockpit drill and insisted everything was OK, and she was religiously doing the MSM routine throughout the lesson. But she wasn’t actually seeing anything useful at all. This is the sort of thing that instructors need to look out for.

What is the correct position for my mirrors?

You want to see as much as possible of what’s going on behind you and to your side, and not leave any unnecessary blind spots.

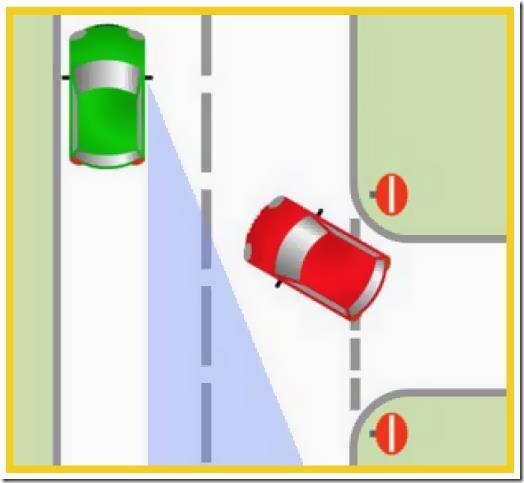

The interior and exterior mirrors’ coverage overlaps behind the car, but there are areas where only one mirror provides useful information – and areas where none of them do (the blind spots). The red car in the diagram is in a blind spot, and would not be visible in any of the mirrors, so you’d have to turn to look over your shoulder to see it (this is a shoulder or blind spot check).

There is no advantage to being able to see birds and aeroplanes anymore than there is to being able to check out the squashed hedgehogs. And it goes without saying that the interior mirror is not for checking your hair and make-up.

How you achieve the correct mirror setting is really up to you, but it makes sense to have a consistent position so that you can see the same space around the car whenever you go out. If the mirrors are too high then you won’t see the lines when you’re reversing into bays, for example, but too low means you can’t see behind you properly when you’re driving, which can be a particular problem if the road undulates (i.e. it is hilly).

I get my pupils to use the door handles as references, as explained above. For the interior mirror, the driver wants to see all of the back window with a slight bias towards their left ear. But remember, this is just a very general guideline that I use – it isn’t written down anywhere that you have to use it.

How much of the car should I see in the passenger mirror?

Almost none of it – just the same as with the one on your side.

Although there is no rule that says they have to be set in a precise way, common sense dictates that the mirrors are there so that you can see what’s going on around you at ground level – not so you can stare at the side of your car. Therefore, you want to adjust them so that you can’t see much of the car at all, and not too much sky or road. Being consistent is a natural consequence of that.

Don’t try to adjust your mirrors too far outwards to try and cover your shoulder blind spots – you won’t be able to do it, and you’ll just create two more of blind spots behind the car. What you’re after is almost continuous coverage from the nearside mirror, through the interior mirror, and across to the offside mirror.

How can I adjust my mirrors to eliminate blind spots?

If you mean the blind spots you need to turn around for, you can’t – not with the standard mirrors fitted to the car, anyway.

The only way to cover your shoulder blind spots using mirrors is if you buy additional piggyback ones that fit on top of your existing mirror housing and which can be angled differently (or those round convex ones you stick on the surface of your existing mirrors. Such additional mirrors are often used by people who can’t turn around properly, or in cases where the driver cannot see behind properly due to the vehicle design. A lot of instructors also use them, but I am not in favour because pupils are unlikely to fit them to their own car, and they just promote laziness when it comes to being safe. I only use additional mirrors if I’m teaching someone with a disability which impedes turning around in the seat.

Unless you have a medical condition or some genuine reason for needing extra mirrors, you should not be looking for ways to avoid checking your blind spots properly. Turning around to look is absolute, but using a mirror is by proxy. A mirror is useful if there is absolutely no other way – but it is dangerous and lazy if the mirror replaces the absolute way needlessly.

My instructor told me the car should fill one third of the mirror each side

I’m sorry, but that is complete nonsense. As I said above, there is no absolutely correct mirror position, but there are plenty of absolutely wrong ones. What point is there in wasting a third of the mirror area just so you can look at the side of the car? I’ve also heard similar nonsense about “two [or three] finger widths” of car being visible, which is also wrong.

Your mirrors are there to show what’s behind you. Adjust them so that they show a tiny sliver of the car, and not too much sky or road.

Can I re-adjust my mirrors for particular manoeuvres?

Yes. My own pupils only adjust it for the parallel park, because I have a method which accurately positions the car relative to the kerb, but I sometimes pick up new pupils who like to drop the mirrors for any reversing (quite a few used to do it when reversing around a corner). If it works for them I don’t try to change it, but if it doesn’t I get them to do it my way. For normal observations, the mirrors don’t need to be moved if they’re adjusted properly in the first place.

If my side mirrors aren’t adjusted properly will I have trouble with parallel parking?

It depends what method you’re using. In order to parallel park you need to know where the kerb is and to judge your position relative to it, so if you’re using your mirrors to determine that, you’ll have problems if the mirrors are badly adjusted, or if they’re adjusted differently each time you get in the car.

This is true of any manoeuvre or situation where you use your mirrors – if they’re badly or inconsistently adjusted then you won’t be able to see what you ought to be able to.

Can I re-adjust my mirrors if I’m on my Part 2 (driving instructor) test?

Yes.

Can I ask the examiner to adjust my mirror for me?

If you have manually-adjustable mirrors, yes. The examiner will not refuse this request. The examiners’ SOP (DT1) says (or used to):

The candidate may ask the examiner to assist in adjusting the nearside door mirror before a manoeuvre. The examiner should not refuse this simple request, and assist the candidate as appropriate. The candidate should not have to lean across the examiner to adjust the mirror.

If you have electrically-operated mirrors, it is a non-issue since you can adjust them as necessary.

Would I fail if I touched (clipped) someone’s wing mirror?

If you mean clipping it with your wing mirror (or any other part of your car), almost certainly, yes! You could fail just for being too close to someone’s wing mirror, so clipping it would be even worse.

Like most things you can never be 100% certain that it would result in a fail – there might be extenuating circumstances – but in all normal cases it would mean that you were passing too closely, and that has its own box on the DL25 Marking Sheet. You’d get a serious or a dangerous fault for it depending on the actual situation.

I clipped someone’s mirror. Does it make me a bad driver?

Only if you keep doing it. Most people have done it at one time or another, but they learn from their mistakes.

If you actually break someone’s mirror, my advice is to let them know. Years ago, one of my pupils went into a narrow gap too fast, panicked when a bus also came through, and clipped someone’s wing mirror when he steered away. I can vividly remember seeing the glass from the other car’s wing mirror fly up as we went past. I pulled him over immediately, and ran back to the other car – which had someone in inside ready to drive away – and apologised profusely, got their phone number, and informed my insurance company right away. None of this crap about not admitting liability – we were at fault completely.

Who are you to tell people how to set their mirrors?

Yes, that question has been asked in those aggressive terms on more than one occasion (including on forums, where instructors are trying to score points off of each other).

The short answer is that that I’m a driving instructor, and one that knows what he’s talking about. If someone hasn’t done it before – and if they’re paying me to teach them – I will give them the correct guidance they need on all aspects of learning to drive. If your instructor isn’t helping you with stuff like this it is probably because he or she doesn’t know the answer, and he’s taught you not to know it either.

What am I checking for when I use the mirrors?

Anything or anyone that you might hit or inconvenience if you move off. The mirrors are only part of it – you also need to check your blind spots, which are those areas not covered by the mirrors.

How should I use the mirrors?

Generally, at least in pairs. Use your own common sense.

For example, if you’re parked on the left hand side of the road and want to move off, you would typically check your inside mirror, offside (right hand) mirror, and right shoulder blind spot to get the maximum amount of information about what is coming up behind you. However, if you were parked on the right hand side of the road then you’d check your inside and nearside (left hand) mirror, and your left shoulder blind spot.

In either of the above examples, if you’d seen pedestrians, children, people getting into cars in driveways, or anything else that could be relevant, then you may well decide to check your other mirror and blind spot as well.

Do I need to check them in any particular order?

Not really, but checking the inside, wing, and blind spot in that order makes the most sense in most cases. If a car is coming up from behind on a straight road it will initially be visible in the inside mirror. As it gets closer it will appear in both the inside and offside mirrors, then move to only the offside mirror. Finally, it will only be visible in your blind spot until it passes you. And in any case, what is in your blind spot is closest to you, so checking that last gives you the most up to date information to act upon.

However, if you know there is a hazard of some sort behind you – cyclists or pedestrians, for example – look in the mirror/blind spot most likely to tell you where it is and what it’s doing as well. You are not going to be marked on which order you check them in as long as your checks are meaningful.

Remember that it is your responsibility to check properly. In extreme cases it may even be prudent to stop and get out of the car. For example, what if you see a small child on a bike, or even a dog, which then disappears from view as you’re about to move off? Where are they? This is especially relevant if you are doing a reversing manoeuvre of some sort.

Should I do a six-point check?

Some instructors absolutely live for routines like this.

If you insist on doing it, as long as your checks mean you don’t move off when someone is behind you, then it doesn’t really matter. Just bear in mind that while you’re doing two/three of the six checks (which are not always necessary), things could be developing in the other three/four (which are). For that reason, I do not teach this silly routine.

Many years ago, I had a pupil who used to do it. She used to say “no one there, no one there, no one there, no one there, no one there, no one there” as she did it. On her test, which she passed, the examiner commented on it by saying quietly to me outside the car: “she’s not very mature, is she?”

The simple fact is that as long as you are certain it is safe to move off, and the examiner knows that you know, that’s all that matters. How you get that message across to him is up to you.

Is it OK if I check all the mirrors every time?

It depends. Although checking all three mirrors to pass a parked car, for example, isn’t a fault in itself, the extra delay that the unnecessary additional check creates could cause problems. The most likely one is that you’ll steer out later and you’ll therefore be looking away from the obstruction at the same time you’re getting close to it. One of the most common faults (and causes of test failure) is passing obstructions too closely.

It’s the same when moving off. If you add unnecessary additional checks, the first one becomes quite stale before you’ve finished the last. If you check your right mirror/blind spot first, someone could turn up while you’re looking needlessly to the left. If that happened – and you didn’t see them – you would probably fail.

If you are doing it because you’re trying to cover all the bases and make sure you don’t miss a check in front of the examiner, or religiously performing the Six-point Check Ritual, it’s the wrong way to go about it. Remember that learners tend to be quite slow with their checks in the first place, and extra ones make them even slower – sometimes, too slow.

If it’s because you used to ride a motorcycle, then as long as you’re aware it isn’t absolutely necessary every time in a car – and if no other problems result – then it doesn’t really matter.

Instructors shouldn’t really be encouraging unnecessary checks, though they shouldn’t be trying to stop it if no other issues are cropping up.

I failed my test for observation when moving off, but I did look over my shoulder

The examiner is watching you to make sure you take effective observations before moving off (and in other circumstances). Just looking isn’t enough. You have to actually see, too. That’s what is meant by “effective”.

Think about it. Looking in two mirrors and over your shoulder involves three head movements, but you could do this with your eyes closed and not see anything at all.

I once had someone on a lesson stop at a T-junction to emerge, look both ways, and then try to pull out in front of a bloody lorry which was less than 20 metres away approaching from the right. They had looked, but not seen.

The problem is that when people don’t appreciate why they’re looking or what they’re looking for, they won’t do it properly. In that case they may as well have their eyes shut for all the good their “checks” do.

The chances are that something similar to this is what happened on your test. Or perhaps the examiner wasn’t happy that you’d have seen something if it was coming (even if it wasn’t) because you didn’t look properly.

Someone found the blog on the search term “what are the chances of passing your test in three months?”

Someone found the blog on the search term “what are the chances of passing your test in three months?” Wouldn’t you just love to have the guts to put one of these on your car?

Wouldn’t you just love to have the guts to put one of these on your car?

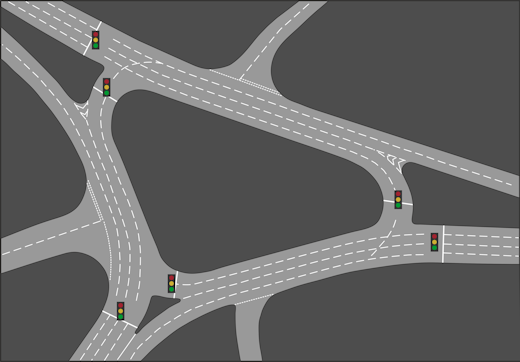

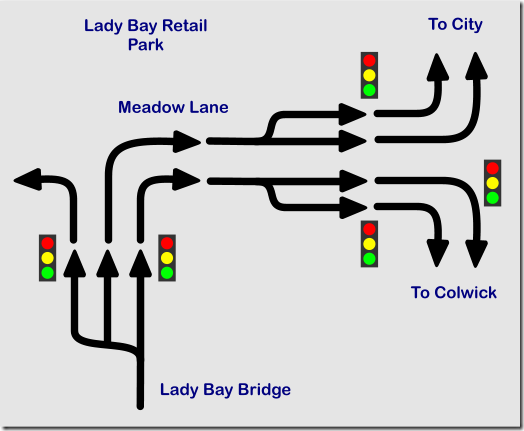

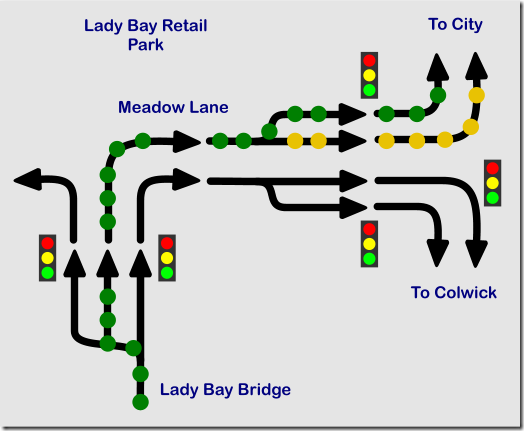

A long, long time ago – while the ink was still damp on my first ADI badge – I discovered that some test routes in Nottingham were going through an old, narrow, one-way part of the city centre. I quickly realised that it would be wrong to expect pupils’ first encounter with these to be on their tests, so I started covering that area on lessons.

A long, long time ago – while the ink was still damp on my first ADI badge – I discovered that some test routes in Nottingham were going through an old, narrow, one-way part of the city centre. I quickly realised that it would be wrong to expect pupils’ first encounter with these to be on their tests, so I started covering that area on lessons. I saw someone post an online comment about having seen “a big school car” driving in the middle lane of a motorway, and then implying that this in some way meant that every ADI who works for that “big school” is therefore pants.

I saw someone post an online comment about having seen “a big school car” driving in the middle lane of a motorway, and then implying that this in some way meant that every ADI who works for that “big school” is therefore pants. This article was originally published in 2011, with updates in 2014 and 2016. It has had a few hits recently, so I’ve updated it again.

This article was originally published in 2011, with updates in 2014 and 2016. It has had a few hits recently, so I’ve updated it again.