It’s 2023, and the warm Spring Bank Holiday weekend kick started interest in this article yet again. It was originally published in 2019.

Note that this article also applies to the JML InstaChill, Chill Tower, and any cooling device that costs under £100 and claims to just run ‘on water’ – even if it is manufactured by someone else.

In quick summary: these devices do not work to anything like the levels claimed. The original article follows.

Early in July 2019, I saw the Chillmax Air advertised on TV in one of those shouty JML ads. That same evening, I was shopping in Asda and saw it on display. I am an idiot for things like this, and bought it on impulse so I could test whether it worked or not.

I’m a chemist, and I know that in order to cool a large space effectively you’re going to need something with a big fan and a special refrigerant. In practical terms, that means a fairly bulky device with a motor-driven compressor, a closed radiator for the refrigerant to pass through, a fan to suck air in and blow it across the radiator, and a wide exhaust pipe through the wall or window to get rid of the ‘removed heat’, and – in some cases – a drain for the condensed water which results from cooling the air. A typical proper air conditioner for a small or medium-sized room will be about the size of bedside cabinet. The Chillmax Air is not much bigger than six CD cases glued into a cube.

If you’ve ever used a normal desk fan you will know that you only feel cooler if you’re sweating a bit. That’s because the fan evaporates your sweat as it pushes air over it, and that evaporation is accompanied by a cooling effect – it’s called ‘evaporative cooling’. If you’re not sweating, you don’t feel the effect. Conversely, if the surrounding air is very humid, then no matter how powerful your fan is, you will feel little or no cooling because sweat can only evaporate if the air has capacity to hold additional moisture (I’ll explain that a bit more later, because it’s what determines whether the Chillmax is any good).

Many liquids exhibit the evaporative cooling effect. In the case of diethyl ether, for example (that’s the stuff they used to use as an anaesthetic), if you force it to evaporate very quickly you can even freeze water (if you do it properly). However, ether is both highly flammable and toxic, so apart from demonstrating it in the school lab (where I remember the fumes gave me a massive headache), it doesn’t have much practical application these days. Early refrigerators used it, which was spectacularly dangerous.

The Chillmax Air uses the evaporative cooling effect of water, and this is much less than with ether – similar to sweat, in fact. The unit consists of a reservoir at the top, which you fill with normal tap water, and this drips down on to a radiator unit which has ten sideways-stacked fibre panels in it through which a fan blows air. The water evaporates from the fibre panels, and the evaporatively cooled air comes out through the front grille. If you believed the ads, you’d be forgiven for thinking you’re going to get frostbite if you sit too close. I knew this wasn’t going to happen, but I wanted to know just how effective the Chillmax was.

When I first set it up and turned it on, the first thing I noticed was that the fan is quite powerful, so you get a good flow of air directed at you – but note that that it’s only a 5″ computer fan, so it can’t beat a proper desk fan for air flow. The air did seem a little cooler compared with what my desk fan was blowing at me, but it also felt ‘softer’ – that’s very important, and I’ll explain later. But the big question was how much cooler was the exhaust air?

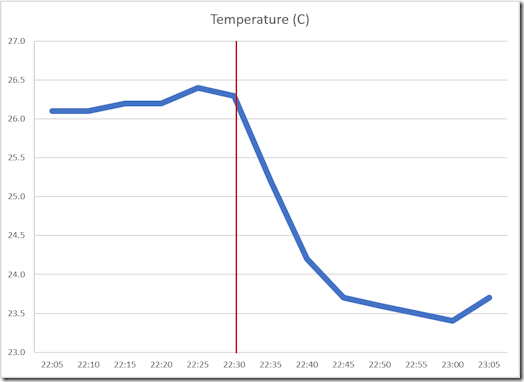

I fired up my trusty data logger and left it in front of my desk fan for 30 minutes for the control data. Then I powered up the Chillmax and moved the logger in front of it for the same period of time. This is what it recorded (the red line is where I moved it).

The ambient temperature where I ran the test was about 29ºC (this was just before the 2019 heatwave kicked in properly). The Chillmax brought this down by about 4ºC.

So, the Chillmax definitely cools the air that passes through it. Let’s work on the assumption that it would be able to get the same 4ºC drop no matter what the ambient temperature was. If your room is 38ºC, pulling it down to 34ºC still means it’s bloody hot. And also note that the Chillmax is physically quite small, so the cooling is very localised – it won’t cool an entire room down, and you have to have it less than a metre from your face to feel anything.

Now, some people might be thinking that a 4ºC is better than nothing at all. And they’d be right if it was just a matter of temperature. But there’s more to it than that. I mentioned that the exhaust from the Chillmax felt ‘softer’. I knew what it was, but my data logger shows it in numbers.

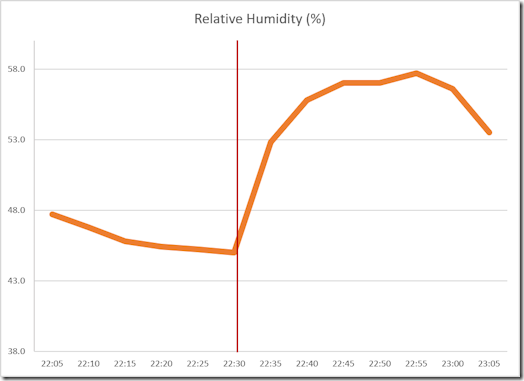

These are the data for relative humidity recorded at the same time as the temperature measurement, above (the red line is where I moved the logger). The humidity went up dramatically – a jump of about 30%RH.

As I’ve already explained, the Chillmax works by evaporating water on fibrous panels by forcing air across them. That water has got to go somewhere, and in this case it comes out with the cooled air as water vapour. In the right light, you can actually see it – it’s essentially fog, so the cooled air is also moistened. And just like when it’s foggy outside, and everywhere gets damp, this water vapour can condense on cooler surfaces. My data logger collected some and began to drip during the test, and I have since discovered that it also condenses on the front grille and can drip periodically, so you’d need to be careful what you had underneath it if you placed it on a shelf. The fan is quite powerful enough to project the drips forward slightly when they drop.

The ambient humidity in the room where I did the test was about 44%RH. The Chillmax sent that up to over 70%RH. It is this elevation of the humidity of the cooled air which really brings into question whether the Chillmax is worth the investment.

You’re probably aware that you can have a hot summer day in the high 20s where it is pleasant and comfortable, but a cooler and overcast day might be horribly sticky – or muggy. That’s because of the humidity, or water vapour in the air.

The amount of water vapour that air can hold varies with the temperature. Cold air can’t hold much, but warmer air can. At any temperature, once you reach the maximum amount possible, any extra vapour condenses out as liquid water – misted up windows, dampness, even drips and pools of moisture on window sills or under lamp posts. In winter, the condensation point is reached very easily, which is why you get your windows all steamed up and everywhere is often damp, but in hotter weather it is more appropriate to think ‘sauna’ (which is why it gets ‘muggy’). This air moisture is what we call ‘humidity’.

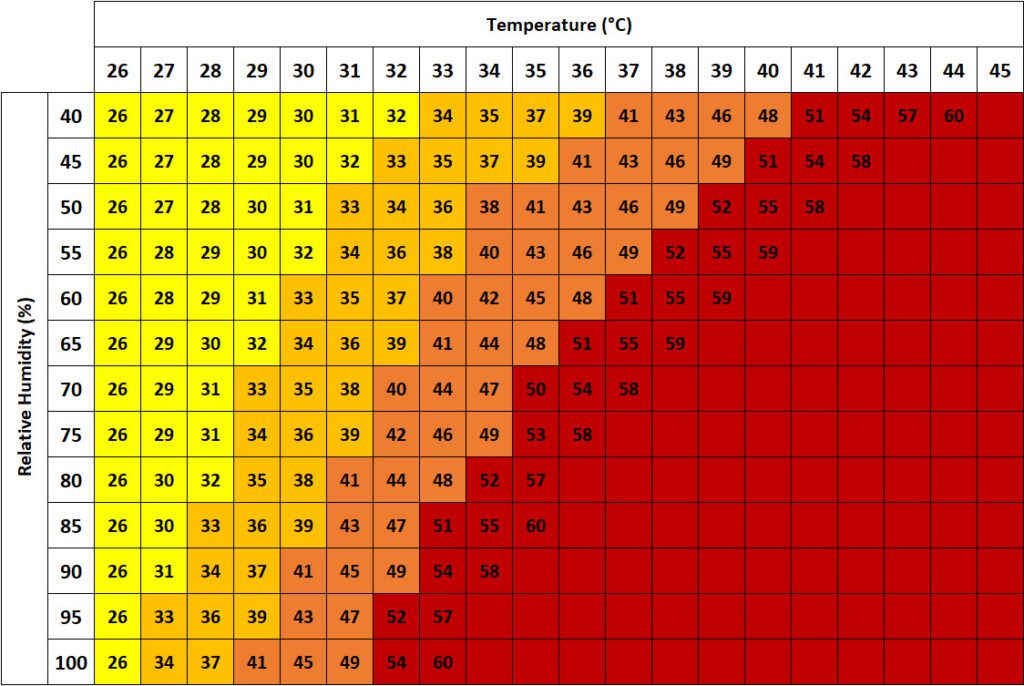

The term ‘humidity’ usually refers to the absolute humidity, which is amount of water in the air. However, the figure most people are referring to is the relative humidity. This is the amount of moisture in the air expressed as a percentage of the maximum amount it could hold at that temperature, hence the units %RH. It’s a complicated subject, but the important factor for us here is that when it is warm or hot, higher absolute humidity is uncomfortable because the amount of moisture in the air relative to the maximum possible is higher. Indeed, you may have seen weather forecasts where they give the actual temperature and the ‘feels like’ equivalent – that’s a reference to the ‘Heat Index’, which takes into account the effect of the %RH. Here’s a graphical chart for that.

As an example, if the air temperature is 30ºC and 50%RH, it will feel like 31ºC, but if the humidity goes up to 80%RH, then it will feel like 38ºC – even though the thermometer still tells you it’s 30ºC.

Another example. If the air temperature is 35ºC, at 50%RH it will feel like 41ºC, but send the humidity up to 80%RH and it’ll feel like 57ºC – even though the thermometer still reads 35ºC.

The calculation for this is complex (you should see how long my Excel formula for it is). It is non-linear, and the increase in ‘feels like’ is greater at higher temperatures. It also contains an element of opinion/perception, which is why there’s no point using numbers above about 60ºC. But the ‘Heat Index’ is what forecasters use. Incidentally, the official health designations for the colours are: yellow – caution; amber – extreme caution; orange – danger; and red – extreme danger. Vulnerable people need to take these into consideration before going out in hot weather.

However, this is where the problems come in for the Chillmax and similar devices. If it’s 35ºC and 40%RH, it’ll feel like 37ºC. Cool the air to 31ºC but send the humidity up to 80%RH, and it’ll feel like 41ºC. So it’s actually hotter in terms of comfort. Do the same comparison when the surrounding temperature is 38ºC, and the ‘feels like’ goes from 43ºC to over 50ºC!

At lower temperatures the Chillmax will produce a slight net cooling effect. But if the air temperature is above about 30ºC (and 50%RH) – which isn’t excessively hot or humid to start with, though it is around the point where you would start thinking about cooling things down – it’ll actually make you feel warmer. And if it is already humid outside, you’ll feel hotter still.

Proper air conditioners remove water from the air they cool. This removal of moisture is why the air from proper air conditioners feels crisp, as opposed to the ‘softness’ of moist air. The Chillmax does the opposite of normal A/Cs, and adds moisture.

Aesthetically speaking, the Chillmax is a cube – more or less – about 15cm along each side. There are two buttons on the top rear, one which changes the fan speed to one of three settings (or off), with a blue LED for each, and another button that turns the night light on or off. There’s a flap on the top front through which you add the water. The radiator system is a plastic-framed insert which you access by pulling the front grille out. It slots in and out easily. You can’t officially replace the fibre inserts in the radiator, but you can buy the whole radiator assembly from JML for £15. My only major gripe is the power cable. The jack plug that goes into the Chillmax is quite stubby and doesn’t go into the socket very far, so it is easy to dislodge it. However, the cable itself is quite long, and the mains plug is a moulded UK type.

JML claims the Chillmax can run for up to 10 hours per fill, but this is likely on the lowest of the three fan speeds, since on top speed it runs out in less than three hours. JML sells the humidification as a positive without relating it to the comfort relationship between temperature and %RH, but note what I said above. If you want to cool down in humid weather, it isn’t just the temperature that needs to come down.

Now. All of the above is an absolutely independent analysis. It came about simply from buying a Chillmax Air, testing it, then understanding what it was doing. None of the conclusions I arrived at were influenced by any other sources – I didn’t look it up first, nor have I had any inclination to do so since I first wrote the article. My measurements were factual, and my explanation was scientific. However, as of 2022 I decided to do just that and look up reviews of evaporative coolers. You might want to look at a few of these links, because I was right.

Do Swamp Coolers Actually Work? | Wirecutter (nytimes.com)

Evaporative Coolers Vs. Portable AC Units: What is right for you? – NewAir

Are evaporative coolers as good as air conditioners? | ProductReview.com.au

10 Things to Know Before Buying Portable Evaporative Cooler (vankool.com)

There are many, many more. And in every case, the relationship with humidity is the key. If it is already humid, evaporative coolers do not work and actually make things worse.

At the time of this most recent edit, it is 20 minutes past midnight on 19 July 2022 and the official Met Office temperature in Nottingham (where I am) is between 28ºC and 29ºC (it was just over 37ºC earlier on 18 July). Humidity is 35%RH, but it is up to 60%RH less than 40 miles away at the next Met Office station. In Nottingham, humidity peaked at 60%RH on 18 July, even if it dropped to under 30%RH at times. And that was outdoors – indoors you can add 30-40%RH without blinking.

Evaporative coolers are a big risk with the humidity we experience in the UK. And especially indoors.

Does it really work?

It does cool the air by a few degrees, so in that sense it works. However, it also sends the humidity up, and in most cases that actually makes you feel hotter and more uncomfortable. In that sense, it doesn’t work.

Will it cool more if I use ice water?

No. Evaporative coolers are not influenced significantly by the temperature of the water used in them. The temperature of the air that comes out depends on the temperature (and humidity) of the air going in, and the science of evaporation. Only this evaporation results in the cooling effect observed.

Will it cool more if I put the filter in the freezer?

It might – while you’re blowing air over ice. But once they defrost, which will happen in a few minutes in the temperatures you’ll likely be experiencing, then no. You’ll also have more condensate to deal with from the melted ice pouring out of the front grille.

You may see reviews on Amazon claiming that freezing the filters (or using ice cubes in the water tank) does give cooler air. Trust me – apart from what I just said about blowing air over ice, it doesn’t. Science is involved, and evaporative cooling doesn’t work like that.

Can I use it to cool my PC?

Someone found this article on the search term “jml chillmax air for pc cooling”. No. Blowing damp air into your PC would be dangerous, potentially expensive, and would only gain you 4ºC at best.

Can you get larger versions?

Until August 2021, the answer in relation to the ChillMax was no. However, I saw an advert (as shouty as usual) for the InstaChill tonight. Unlike the ChillMax, which is the size of a small table top radio, the InstaChill is the size of a bedside cabinet. And you can certainly get larger evaporative coolers from other manufacturers. The working principle is identical, except that the larger the surface area of water, and the greater the airflow over that water, then the greater will be the possible drop in temperature at the front end (and the more moisture being pumped out to increase the humidity). However, cooling effectiveness is influenced greatly by the RH of the air going in.

If the air is very dry, then a large evaporative cooler might be able to drop inlet air at 30ºC down by as much as 10ºC. However, if the inlet air is very humid, the temperature drop could be as little as 1ºC. In the UK, the realistic temperature drop you could expect on a non-humid day for a large cooler would be around 5-6ºC, but on a sticky day you’d only get about a 3ºC drop.

Suppliers of these devices say that they need good ventilation or extraction, and I would imagine that’s so the humid air can escape. If you’re evaporating more water to get better cooling on larger devices, you’re also producing a lot more water vapour, so the cooling effectiveness will decrease as the humidity rises unless you vent it somehow. Be careful if you read any of the reviews on these things – people may have noticed cooling in already cooler conditions, but trust me – if it’s very warm and humid, you will not notice any effect.

People say it works

Be careful when you read those one-line reviews. If you test it when it’s only 20ºC outside – as many of these people have – then yes, it blows noticeably cooler air at you. But science is involved, and at temperatures above about 28-30ºC you’ll actually feel hotter. The fact that it increases humidity is the key factor. Remember that the reason you even found this article was probably because it’s over 30ºC outside – the more above that it is, then the more hits I get.

So, does the Chillmax/InstaChill work?

They cool the inlet air by several degrees. But they send the humidity of that air up considerably, and this cancels out the benefits of the cooling effect when it is very hot. The ‘Heat Index’ is the key detail, as explained above. In the case of the InstaChill, it will add a lot more humidity than the ChillMax, and as I have explained and demonstrated, the ChillMax is bad enough when it comes to increasing the ‘feels like’ temperature.

Only the air being directed at you is cooler. Once that slightly cooler air has passed through warmer air, it’ll be close to ambient again. The device cannot cool down a room. It’s far too small for that.

Humidity can carry much further, though, and it hangs around unless it condenses out somewhere. So in a small room, you could easily increase the ‘ambient’ RH without any cooling at all, and that will make it feel even hotter. If it is already hot, the amount of water vapour the air can hold before reaching 100% RH will be substantial. The increased humidity of the outlet air does produce localised condensation, so you have to be careful to keep these devices away from electrical sockets where they might drip on them, and there is also the risk of dampness in your home and the problems that it can cause. The devices also contain a significant volume of water when full, so you don’t want to knock them over.

Should I buy one?

My advice is to buy a proper air conditioner (A/C). If anything costs under £200 it is not a proper A/C. However, it is possible some people might find the minor cooling effect and increased humidity of the Chillmax/InstaChill (and similar devices) beneficial, so the choice is yours. But for real cooling and dehumidification when it is hot, it has to be a proper A/C.