I wrote this article in 2013 after I’d seen someone desperately trying to complicate the subject by claiming that the Emergency Stop isn’t in DT1 (the examiners’ internal guidance document). Just for the record, that document contains the following section:

1.31 EMERGENCY STOP

An emergency stop should be carried out on one third of tests chosen at random. It can normally be carried out at any time during the test; but the emergency stop exercise MUST be carried out safely where road and traffic conditions are suitable. If an emergency has already arisen naturally during the test this special exercise is not required; in such cases the candidate should be told and a note made on the DL25.

With the vehicle at rest the examiner should explain to the candidate that they will shortly be tested in stopping the vehicle in an emergency, as quickly and safely as possible.

The warning to stop the vehicle will be the audible signal “Stop!” together with a simultaneous visual signal given by the examiner raising the right hand to face level, or in the case of a left hand drive vehicle, raising the left hand. This should be demonstrated.

The examiner should explain to the candidate that they will be looking over their shoulder to make sure it is safe to carry out the exercise, and that they should not pre-empt the signal by suddenly stopping when the examiner looks round, but should wait for the proper signal to be given. To minimise the risk of premature braking, examiners are advised to ask the candidate if they understand the ES instructions.

The emergency stop must not be given on a busy road or where danger to following or other traffic may arise.

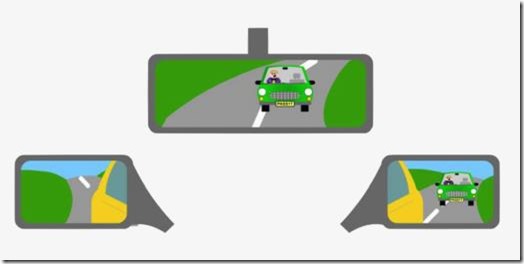

It is essential that examiners take direct rear observation to ensure that it is perfectly safe to carry out the exercise. They must not rely on the mirrors.

If the exercise cannot be given within a reasonable time the candidate should be asked to pull up, care being taken to choose the right moment as the candidate will have been expecting the emergency stop signal and may react accordingly. They should then be advised that the exercise will be given later and that they will be warned again beforehand. Alternatively, if conditions ahead are expected to be favourable, they should be reminded that the exercise will be given shortly, and the instructions repeated if necessary.

If a candidate asks whether they should give an arm signal, they should be told that the command to stop will be given only when it appears that no danger will arise as a result of a sudden stop, but that they should assume that an extreme emergency has arisen and demonstrate the action they would take in such a case.

The emergency stop exercise must not be used to avoid a dangerous situation.

It’s worth pointing out a few things that worry learners, all of which are mentioned above or in the rest of DT1:

- you will not be asked to do it on a busy road

- the examiner will check behind first, so you don’t have to

- having to do it in a real situation could count as having done it on the test – the examiner will tell you

- it will not be done as part of Independent Driving

Furthermore, DT1 adds:

ABS – Anti-lock braking system.

Note: Anti-lock braking systems (ABS) are being fitted to an increasing number of vehicles. Examiners should not enquire if a vehicle presented for a test is fitted with ABS.

Most ABS systems require the clutch and footbrake to be depressed harshly at the same time to brake in an emergency situation; therefore a fault should not be recorded purely for using this technique with a vehicle fitted with ABS on the emergency stop exercise. On the emergency stop exercise, under severe braking, tyre or other noise may be heard, this does not necessarily mean the wheels have locked and are skidding. Examiners should bear these points in mind when assessing the candidate’s control during this exercise. Further advice regarding ABS is given in the DVSA publication ‘driving the essential skills’.

I’ve mentioned ABS and the Emergency Stop before because of people trying to complicate it simply as a result of their own lack of understanding. I’ll repeat what I said in that article: when it says to press the brake and clutch at the same time, it doesn’t specifically mean that both feet must go down as if they were glued together at the ankles. The thing you have to remember is that the clutch will begin to release as soon as you start to press the pedal, and the brakes will start to bite as soon as you start to press them. Neither are digital switches – they are analogue devices, which means that there is significant travel of the pedals to achieve varying amounts of the relevant effect. So if the clutch releases more than the brakes are braking, the car will take longer to stop because the effect of engine braking is removed. For that reason, you really want to be braking hard first, then depressing the clutch a fraction of a second later when executing an emergency stop. The whole process happens in less than a couple of seconds anyway.

It still amounts to pressing both pedals “at the same time”, but this distinction relates back to the older method of cadence braking (on non-ABS cars), where you had to pump the brakes and slow down in stages, THEN put the clutch down right at the end to avoid stalling. In this case, you were not pressing both pedals at the same time, and doing so would most likely have been a serious fault on someone’s test.

Trust me, if your mum walks out in front of you and you need to do an emergency stop to avoid hitting her by a hair’s breadth, not utilising engine braking properly could make all the difference between a big sigh of relief or a trip to the hospital.

It doesn’t matter if the ABS kicks in (and makes a noise outside, with vibration on the brake pedal inside) during the exercise. As long as the driver is in control and stops the car promptly then the Emergency Stop will have been completed satisfactorily.

The Emergency Stop will nearly always be carried out as a totally separate exercise on the test, though if you have had to do one in a real situation (possible but highly unlikely for most candidates) then the examiner may count that as having done the exercise if you were one of one in three who gets it. For the exercise proper, the examiner will ask you to pull over and he will then explain as follows (again, taken from DT1):

Pull up on the left please (either specify location or use normal stop wordings) Shortly I shall ask you to carry out an emergency stop. When I give this signal, (simultaneously demonstrate, and say) ‘Stop’, I’d like you to stop as quickly and as safely as possible. Before giving the signal I shall look round to make sure it is safe, but please wait for my signal before doing the exercise.

Do you understand the instructions?

Once you have completed your Emergency Stop, he will say something along the lines of:

Thank you. I will not ask you to do that exercise again. Drive on when you are ready.

It’s that simple. And the decision over what is and isn’t acceptable lies with the examiner.

What would be a minor (driver) or serious fault on this manoeuvre?

The procedure as I teach it is as follows (immediately after the STOP command):

- brake firmly

- declutch just after

- keep both hands on the steering wheel

- once stopped, apply handbrake

- put into neutral

- look all around

- relax

Then, once the instruction to drive on is given:

- put into gear

- gas/bite ready

- look all around

- if safe, release handbrake and drive off

Possible driver (minor) faults might include stalling, going for the gear lever or handbrake before the car stops, or not looking all around properly after you’ve stopped (though that last one is rare).

Possible serious faults might include getting into a mess/panic if you stall, not stopping quickly enough, putting the clutch down before the brake, or not looking all around at all before you move off (this is more common).

Some faults might be only minor in some cases, but become serious if other traffic is around. For example, stalling before you move off and not checking all around again. Or if stalling/panicking causes a hold up for traffic. Or moving off before you’ve looked around properly and someone is overtaking you. The examiner’s decision is what counts because every situation is different.

If you do it right – or even close to being right – on your lessons you’re almost certainly not going to fail your test over it. I’ve never had anyone fail for it. So make sure that you can do it right on your lessons.

Will I fail if I stall on the emergency stop?

No, you shouldn’t if you react appropriately by making the car safe, then get it started again promptly. It will usually be marked as a driver fault. However, you are on test and you might panic and do something else wrong which could result in you failing.

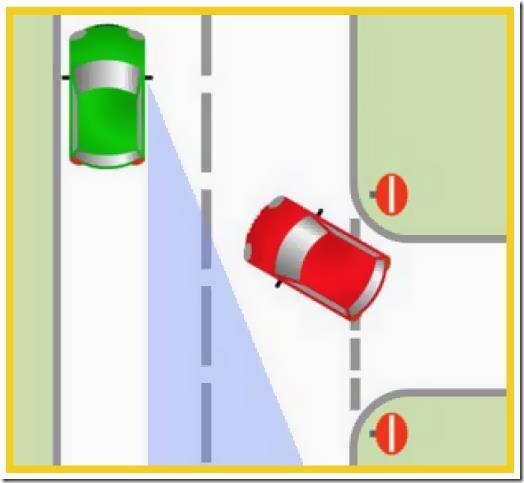

Do I have to pull over when I do the emergency stop?

No. That would defeat the purpose. The idea is to stop as quickly as possible, whilst maintaining control and safety. If you waste time trying to pull over you’ll travel further, and so won’t stop quickly enough.

Imagine your brother or sister (or pet dog or cat) runs out a few metres in front of you while you’re driving along. That’s why you want to stop as quickly as possible, and to hell with what’s going on behind you (the examiner will check to make sure it’s safe by looking behind – you don’t have to).

Once the exercise is complete, you will drive on normally unless the examiner specifically asks you to pull over – which he might, since pulling over then driving off again is a separate thing that is being assessed on your test.

Should I signal when I move off after an emergency stop?

In most cases it isn’t necessary, and you certainly don’t want to be doing it before you’ve looked to see if anyone might benefit. However, if you look around and decide that you should signal – for a pedestrian perhaps, or if someone is coming towards you from either direction – then do it (make sure you signal right and not left).

Why shouldn’t I use the handbrake to stop?

Depending on how old you are, you may remember from certain action movies that the characters involved in car chases sometimes brake, skid the car around, then drive off the other way. What they are doing is called “a handbrake turn”.

The handbrake usually only operates on the rear wheels, and if you are driving along and pull it sharply it can lock the wheels, and that causes them to skid. Since only the back wheels lock, the rear of the car spins around because for all practical purposes the rear wheels are not gripping the road surface.

It’s all well and good if you’re doing a stunt for a movie shoot, but on roads where there are other road users it is incredibly dangerous. Imagine an emergency situation, where you need to stop as quickly as possible, and usually in a straight line. You aren’t going to achieve that if the rear wheels spin out and are not gripping the road surface. At best, you’ll stop over a much longer distance because the handbrake isn’t designed to stop the car in the first place. At the worst, the car will spin out of control and you might hit something or someone – or even roll it.

On top of that, the ABS on modern vehicles functions via the footbrake (which is hydraulically controlled through the car’s on-board computer), not via the handbrake. In a handbrake stop you have no ABS functionality (the electronic handbrakes in modern cars usually won’t operate when you’re moving anyway).

If you apply the handbrake before the car has stopped in the Emergency Stop exercise you’re almost certainly going to get a serious fault for it.

Can you stop using the handbrake in any other situation?

The classic example is if your normal brakes fail for some reason – you press the footbrake and nothing happens. Your only option is to slow down and stop using the handbrake (noting the comment above about electronic handbrakes not working when you’re moving).

It happened to me many years ago when I’d flushed my brake system, but left an air lock in it somewhere. I came to a T-junction and the car wouldn’t stop, so I used the handbrake to slow it down. Fortunately no one was coming, because I couldn’t stop in time for the junction, but I did prevent the car ending up in someone’s living room!

I’m an ADI. How should I teach the Emergency Stop?

You really ought to know this. It isn’t rocket science. What I do is run through skids and how to deal with them, the factors likely to cause them, and so on. I have a few stories about when unexpected things have happened to me (like the time I was in a column of traffic driving at 60mph in the Cotswolds and a herd of deer ran out about 5 metres in front of the van at the front, who slammed into them because he couldn’t do anything). Then I explain the Emergency Stop procedure, which is basically as follows:

- I give the signal

- You brake hard, then put the clutch down – IN THAT ORDER

- Put the handbrake on and put it in neutral

- Look all around

When I (or the examiner) says to drive on:

- Put it in gear and get ready to move off

- Look all around

- If it’s clear, release the handbrake and drive off

Looking all around – and that includes both blind spots – before you move off is critical because traffic or pedestrians could be passing either side of you. If you just glance in your mirrors after you’ve stopped you tend to get away with it, but if you try that as you drive off then it’s pretty much a fail. No guarantees, of course, but if you look properly it won’t be an issue.

“Locking the wheels is always a danger in an emergency stop. A vehicle fitted with abs requires the driver to do what?”

This one keeps coming up as a search term used to find the blog – pretty much the exact same words every time. I suspect someone somewhere is copying a question from their training materials to research the answer.

It is explained in this separate article.

I like to feel as though the ABS is about to kick in when a pupil stops. If the ABS does kick in a little, even better. But I don’t want them stamping hard on the pedal.

This article was originally published in 2011, with updates in 2014 and 2016. It has had a few hits recently, so I’ve updated it again.

This article was originally published in 2011, with updates in 2014 and 2016. It has had a few hits recently, so I’ve updated it again.

An email alert from DVSA advises that from 10 October 2018, the timings of driving tests will be changing for one day each week so that examiners can receive appropriate training and development. Timings on other days will remain unaltered.

An email alert from DVSA advises that from 10 October 2018, the timings of driving tests will be changing for one day each week so that examiners can receive appropriate training and development. Timings on other days will remain unaltered.

I first published this back in 2012 after someone had found the blog on precisely that search term!

I first published this back in 2012 after someone had found the blog on precisely that search term! Take Mallaig in Scotland

Take Mallaig in Scotland Statistics are a statement of what did happen. They are not probabilities – a prediction of what will happen.

Statistics are a statement of what did happen. They are not probabilities – a prediction of what will happen. Just a word of warning to anyone taking their test between 16 July and October 2018. There’s a good chance you’ll have someone sitting in the back when you do your test.

Just a word of warning to anyone taking their test between 16 July and October 2018. There’s a good chance you’ll have someone sitting in the back when you do your test.